This story originally appeared March 1, 2003, seemingly just yesterday but 21 years ago. It’s now 71 years since two teenage boys left their parents and eight siblings on the family farm in a Germany less than a decade removed from the end of its second world war and still reeling.

Though the trip that brought them halfway around the world was arduous, leaving the boys standing momentarily alone on a railroad platform in an unfamiliar land a world away but remarkably similar to what they so recently left, both boys found a good fit here almost as soon as their Aunt Rosie Neumayer, step-grandson Arnold Fessler in tow, gathered them up at the Bonners Ferry Depot and introduced them to the rest and best of their lives.

Being the younger, Al went to school and at Bonners Ferry High School found his future in education and athletics, playing football as a Badger and all four years at Eastern Washington University and coaching football, wrestling and track throughout his long and storied teaching career.

Al died of lung cancer in November, 2006, his wife, Margaret, died in 2023.

Because of the war, John had but a year and a half’s formal education. By war’s end, 11-year-old John was already working. His father later said he should take up a trade. so John took an apprenticeship, learning while he lived with and worked for a butcher/meat cutter/sausage maker and his family.

His dad’s advice served John well, as he went to work as a butcher soon after arriving in Bonners Ferry and he plies his trade yet today in his own custom butcher shop on the family farm he also still works, raising cattle and hay. Hunting season is a busy time, with the lights burning, the saws humming and the grinders churning deep into the wee hours of morning, turning the take of many of his friends and neighbors into freezers full of custom-cut wrapped meats to last the year ahead.

From the moment he arrived John Alt has been consistent, almost a force of nature. Few could hope to keep up with him, let alone outwork him, He is in preternatural good spirits, his brow seldom clouded. He holds friendships dear, his family closest to heart.

From being made welcome after stepping off the train by Rosie and young Arnold, now 93, John has nurtured life-long friendships, not only with individuals, but with entire families. The Ehrmantrout and Lefebvre families who did so much to help he and Al, and later brother Erwin, fit in and become valued members of their community and their new country, Rosie’s stepsons Alois (Ott) Neumayer and his wife Nettie, who became as close as second parents and helping Rosie, their childless widowed aunt, adapt to having two young brothers in her household.

John didn’t just work, he served, enlisting in the Idaho Army National Guard in 1956, first as a truck driver and later as first cook and mess sergeant. His stolid, rock steady character while in uniform was appreciated and admired and when, in 1964 he needed two people to appear before a judge to testify on his application for citizenship, officers Kenny Mendenhall and Milt Hengel were honored. It wasn’t long before John raised his right hand, swore to uphold and defend the Constitution of the United States and became a naturalized U.S. citizen. Officer Bill Mackey was a close friend and mentor to John until Bill’s passing several years ago.

John retired from Boundary County Road and Bridge, where he ran heavy equipment, 28 years ago, in 1996. To this day, he still gets up early of a morning and puts in a workday that would wear out even the strongest of men in the prime of their lives. He stops to help neighbors when help is needed, pitches in without hesitation whenever called upon to give back to this community he so loves.

John Alt will celebrate his 90th birthday at 2 p.m. Saturday, October 5, with a feast cooked up by the cousins at Rotary Park, 2043 Lions Den Road, Bonners Ferry.

All are invited to bring their appetites and help celebrate … just leave enough room for the desserts by Jenny Fessler and Jolene Neumayer Tarr!

Brothers celebrate 50 years in U.S.

March 1, 2003

By Mike Weland

Their memories are as clear as yesterday, yet it was 50 years ago this month that both John Alt, then 17, and his brother Al Alt, then 14, set foot in Bonners Ferry after an arduous journey that took them away from a nation still suffering the ravages of war.

John, Al and their eight other brothers and sisters worked on the family farm near Waldmunchen, Germany. Elsewhere in that country, Aldoph Hitler rose to power and set the nation on a misguided path to war and ultimate defeat.

Before the war, a few of the more prosperous farmers had a tractor to help with the back-breaking work; as the war progressed, the tractors fell idle for lack of fuel and work in the fields was done with oxen or horses. Before the war, food was scarce, but farmers could set aside enough of what they produced to feed the family. During and after the war, even that small luxury was taken away.

Sitting in John’s dining room on a brisk Saturday afternoon on his 200-acre farm in Paradise Valley, John and Al, a retired teacher from Sandpoint, with their wives, Linda and Margaret, at their sides, the memories of their childhoods through World War II came vividly, along with a sense of wonder at the whims of fate.

The Alts didn’t have a tractor, and the children began working as soon as they were big enough to pitch in. Their home was old; neither John nor Al knew when it had been built, but it had seen over 200 years. They didn’t have much in the way of extras, but by their own sweat and toil, they didn’t suffer extreme want … until Hitler demanded every bit of that nation’s produce to feed his war effort.

“You couldn’t buy food,” John said, “Before farmers had what they raised, but once the war started, if you got caught butchering for your family, you were fined, and the meat was taken away. I remember right after the war started; the police came to a neighbor’s farm on a motorcycle with a sidecar; another neighbor had turned him in for butchering a hog. Hitler had spies everywhere. It got worse as the war went on. And after the war, there was just nothing left. There were people stealing.”

Many farmers were later jailed, to be liberated only when U.S. troops arrived.

Because there was no longer enough to feed the family, John was sent to live and work on a farm owned by two of his uncles. They had a bigger farm and no children. As the war raged on, John worked for his uncles as a farmhand. At age 11, John had effectively set out on his own.

In going through old photo albums that Saturday afternoon, John came across a sepia portrait of a young German soldier. John remembers him well, and tells Linda he wants the picture enlarged. The boy, just a little older than John, was a friend from a neighboring farm called up to serve in Hitler’s Army. Three months later, he was dead. Both John and Al remember the names of many others who shared that fate.

John remembers tasting candy and gum for the first time in his life when the U.S. Army came through their farm in a convoy that paraded by the house for over a day and a half, knocking down a barn that had stood forever. Al still complains that he didn’t get any, even though his first taste of sweets a few years later would have serious consequences. Even now, though, it’s the food of his homeland he remembers, simple and scarce though it was.

“I still miss the bread and sausage,” Al says, smiling.

After the war, John recalls farming at the Czechoslovakian border. “His” side of the border was patrolled by U.S. soldiers; Russian troops patrolled the Czech side. He recalls often talking to Russian soldiers as he worked the fields. One day, he said, he heard shots from the Russian sector, and from where he was he could tell there was a disturbance, though he had no idea what was going on.

About two weeks later, three bedraggled men slipped across the border and began asking about their three companions; all six were German soldiers who’d escaped from a Russian POW camp over a year earlier.

They’d make an incredible trek through hostile country, and just when freedom was in sight, they reached an impasse. Three of the men, lured by the seeming easy course down a valley to finally reach their destination, insisted they could make it.

The other three felt it looked too easy, and insisted on staying to high around, away from people. Unable to agree on a path, they agreed to split up.

The three who chose caution survived; the shots John heard were the other three being gunned down as they made their final dash for freedom.

After the war, people in Germany were starving. John began a three-year apprenticeship as a butcher and meat cutter. In those days, he said an apprenticeship was little more than slavery, three years of hard labor for the right to join a profession. His job included tending the team; he’d rise at 4 a.m. to feed the horses, and then hitch them up for the morning deliveries. His day stayed full most often until eight or nine at night, day in and day out.

Germans had quotas for emigration to the United Sates, and those hoping for emigration had to have a sponsor to take them in. The chance to set sail bode well not only for those embarking, but for the families they left behind as well. In the Alt household, it was the only hope. Though none of the ten children had never been more than 10 kilometers from home, the distance they could travel on a bicycle or by team, the family aspired to send John and his older sister, Rosina, to the United States; their aunt Rosina Neumayer, who’d emigrated to the United States in 1923, their sponsor.

After reams of paperwork and months of waiting, John and Rosina Alt were set to embark, but then Rosina became engaged to be married. So, the paper chase started anew, with Al taking his big sister’s place on the application.

John had been an apprentice for 2 1/2 years when the paperwork was finally complete; he walked away without hesitation to go to America. He and his little brother said what all thought were their final goodbyes and left Waldmunchen. They rode the train three days to Bremen, then set out for Bremerhaven, where another paperwork assault awaited. At last, they were ready to set sail.

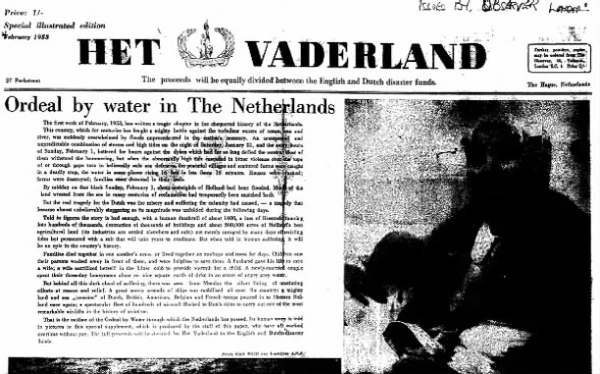

They departed Bremerhaven by ship on January 28, 1953; setting sail into the teeth of one of the worst North Sea storms of the century. In Europe, dikes burst in Holland, 100,000 people were left homeless and 1,800 people were killed.

They departed Bremerhaven by ship on January 28, 1953; setting sail into the teeth of one of the worst North Sea storms of the century. In Europe, dikes burst in Holland, 100,000 people were left homeless and 1,800 people were killed.

It wasn’t until years later that John and Al learned their mother had mourned their passing, convinced they’d been lost at sea.

But, before the storm hit and while seas were yet calm, Al had a self-inflicted storm to endure. Al, age 14, having never tasted ice cream, he became infatuated; both at its taste and its seemingly endless supply.

He ate so much he got sick. Having never been to sea, the ice cream illness was compounded by a three-day bout of seasickness. When the ship started tossing, John awoke to find Al on the floor of their berth thrown out of bed and too weak to get back in.

John doesn’t talk much of it, but said he remembers that part of their voyage as being rough. They didn’t learn the extent of that storm until they recently happened to watch a documentary on the winter of 1953; the year that eight hurricanes buffeted the Atlantic and the year that weathermen worldwide adopted the tradition of giving the fierce storms the names of women.

John more vividly recalls the time after the seas calmed and Al’s seasickness subsided; like the boys they were , he said, they were intrigued by the ship, and set out to explore every facet of the liner, going below decks to the engineering compartments and looking with awe at the mighty engines, exploring the galleys and decks, everywhere the able seamen allowed them to go.

On February 2, the ship reached port and John said Al found themselves in New York City’s Grand Central Station; alone and knowing nothing of the language of their new country. In New York, they boarded a train, and after over 10 days of nothing but ocean aboard a storm-tossed ship, they found themselves crossing unimaginable wide-open country, perched on wooden slats in a gently rocking train. In Chicago, they “bought” a jar of pickles, leaving money they thought sufficient lying on the counter.

While awaiting the train for the next leg of their journey, they explored the big city afoot, walking for hours in awe of the sights.

Back aboard the train rolling across the western plains, they devised a method of ordering in the diner; they’d wait patiently for a particular woman and her daughter to be served, take a table nearby, and when the waiter asked what they’d have, they’d just nod toward that table … an unspoken “we’ll have the same.”

Though he’s been across it many times since, Al said he is still awed by the vastness of the United States.

On February 15, the train pulled into the depot at Bonners Ferry, Idaho, and the two stepped down to be greeted by Aunt Rosie and Arnold Fessler. Though they’d never met, both John and Al knew Aunt Rosie right away; she looked remarkably like Mom.

While Aunt Rosie left before the troubles began in Germany, she had a similar story to theirs; she’d emigrated to Wisconsin in 1923, also sponsored by an uncle, and had moved to California before marrying Karl Neumeyer and moving to Bonners Ferry. Amazingly, Karl’s family lived less than 20 kilometers from the Alt family in Germany; the two families had never met.

Rosie, a housekeeper at the Catholic Parish in Bonners Ferry, took them to the church for their first home-cooked meal in their new country; chicken fried steak. There was two feet of snow on the ground; the weather was brisk. Yet the weather and the country, remarkably similar to that where they’d been raised, made them feel at home. A few days later, they walked into downtown Bonners Ferry for the first time, and John saw two big cats strapped to the hood of a Jeep parked on Main Street.

As he stood looking, Bob Collyer came by and told him they were cougars; shot by that hunter right over there. John was impressed; amazed that in this country you could actually go out and hunt. In Germany, you couldn’t even kill your own pigs without approval.

Unbeknownst to them, Warren Truesdell, a notary, was helping Aunt Rosie traverse the final slew of paperwork pertaining to John and Al’s emigration. It took hours, yet when Rosie asked how much she owed, Warren replied, “Just bring those boys in here so I can meet them.” The three became fast friends.

Al’s first job in the U.S. was digging graves for Mike Fessler at the Bonners Ferry cemetery; he was enrolled at Bonners Ferry High School and learned that he loved two things; the freedom to learn and the freedom to play sports. In German, he loved soccer, but chances to play were rare. Frivolity was frowned on, and there was always work to do. At Bonners Ferry High School, his strength and athleticism led him to standout seasons in football, boxing and track. He graduated in 1957 and went on to the Eastern Washington College of Education, which later became EWU, and earned his teaching credentials.

John went to work cutting meat at Don’s Cafe in Bonners Ferry, a position he held for over 13 years. While there, he met Linda, a college girl working for the summer … they wed in 1967 and Linda has yet to finish school. After Don Beatty died, John stayed on at the cafe for another year and a half, staying true until Don’s wife was able to sell the business.

John next engaged in construction, working in Montana, while Al embarked on a career in education. Al began teaching and coaching in Coeur d’Alene, and then accepted a fateful assignment that would lead him to his wife and to a return to his first home.

Margaret grew up and went to college in New York, and took up an offer to serve as a teacher at military bases around the world. Her first posting was to a military base in Newfoundland, where she met and married Al, who’d signed up under the same teaching program. They next went to the Azores, where their eldest son, Mike, was born, and then they were posted to Germany.

At that time, most teachers in the program were assigned to schools in northern Germany; by some twist of fate, Al and Margaret were assigned south, less than 80 kilometers from the home he grew up in.

His brothers and sisters in Germany met he, his wife and family; he finally learned that his mother thought him and John dead in the storms of the year they departed. She’d never expected to see him again. While they were stationed in Germany, their youngest son, James was born … so close to his father’s first home.

Al, Margaret and their family returned to the United States and shared the good news of their re-established ties with John and other members of the family who’d later emigrated to the U.S.; Erwin, who came to Bonners Ferry in 1955, and Herbert, who came in 1960 and now lives in Spokane.

John, who began buying what is now his farm in Paradise Valley in 1962, worked for 28 years at Boundary County Road and Bridge and served his new country for 12 years in the Idaho National Guard.

Upon his return to the U.S., Al began teaching and coaching at Sandpoint High School; retiring in 1997 after over 26 years. Their son, James, majored in German studies and spent a year in Munich.

John, Linda and their children have likewise returned to visit Dad’s home; they’ve also opened their home to nieces and nephews from Germany who come to visit the United States. John’s son, Don, is a hunting nut, and he loves taking his cousins to his favorite places; the bonds continue to grow through yet another generation.

For John and Al, it is a wheel that keeps turning; a wheel to a new country that never stopped giving; yet a country that lets them celebrate the place they came from.

Aunt Rosie, who came with help from her uncle, made it possible for John and Al to escape unimaginably harsh times; John, Al, Erwin and Herbert now invite their siblings and their sibling’s children to visit them; not to escape, but to enjoy.

For their family left behind, life is good. Their brothers and sisters, Rosina Ederer, Joe, Ella Bauer, Franz, Anna Kraus and Karl; are all successful. The farm is now among the most advanced in Germany, boasting a beautiful new home; German farms are among the most advanced in the world. When they visit their homeland, they’re amazed at the affluence; enough fuel; stores which offer all you can afford to buy; food in plenty.

The bread and sausage are still the best in the world, and the rest of the world is a lesser place because it’s never so good as it is at home. Yet, neither John or Al easily tolerate everything about this land of plenty; a scrap of food left on a plate or waste in any face of our society earns dour looks and chiding remarks.

Linda and Margaret, both raised in the U.S., know the travails the men they love endured to become such good, solid U.S. citizens; they delight in learning more of their families-in-law. On that Sunday afternoon, fresh snow gleaning just outside the window, both learned aspects of the tale they’d never known.

John summed it up best.

“There couldn’t have been a better place to come to than here,” he said.

Another story of our neck of the woods.. Thank you for writing this history, and may each of you enjoy the event at one of the most blessed locations of the country.