By Clarice McKenney

The night before Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, Boundary County residents were inspired by a live performance featuring the life and courage of one Black activist from the Civil Rights Movement. Seattle resident Rosslyn Cornejo has performed the past three years for middle school and high school audiences with the history performance group called Living Voices. Her live performance included historic television footage from key dramatic moments in the Civil Rights Movement.

About 50 adults attended the performance provided by the Boundary County Human Rights Task Force at the Kootenai River Inn in Bonners Ferry.

Cornejo asked the audience to call out names from the Civil Rights movement, and of course Martin Luther King, Jr., John Lewis and Rosa Parks were first among them. Ruby Hollis, whom she went on to portray, was a lesser-known but influential activist in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

“Civil Rights are similar to Human Rights guaranteed by the US Bill of Rights,” Cornejo told the crowd, and they include the right to food, safety, shelter and freedom. “After the Civil War, the US government said that all discrimination against Blacks was illegal, but after a brief time when Blacks were even elected to Congress, the government abandoned Blacks’ protections of their civil rights. Especially in the southern states, many Whites discriminated against Blacks, severely restricting them under the Jim Crowe laws.”

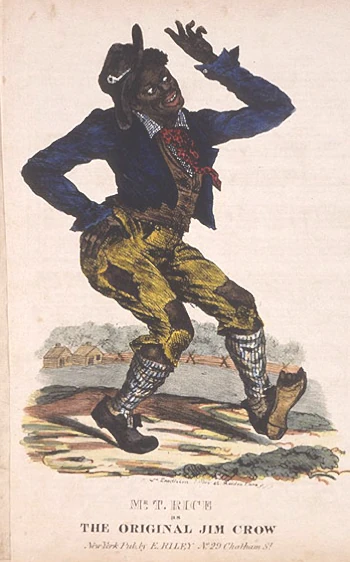

Audience member Rob McKenney asked who Jim Crow was, and Cornejo said he was a made-up character and showed the group a gross caricature, supposedly representing a Black man. Tattered clothes and shoes, awkward gestures and strange stance was to make the figure look less than human.

Audience member Rob McKenney asked who Jim Crow was, and Cornejo said he was a made-up character and showed the group a gross caricature, supposedly representing a Black man. Tattered clothes and shoes, awkward gestures and strange stance was to make the figure look less than human.

When she was a child, Ruby Hollis and her best friend Jackie had no racial awareness, let alone hatred for each other’s race. One day, Ruby followed her friend into the local theater to see a movie, but theater employees chased Ruby upstairs, not allowing her to sit on the main floor with Jackie. Ruby was confused and hurt, and her mother told her daughter that Negroes can only sit in the balcony. Soon after this, Jackie’s family forbid her to associate with Blacks.

One of the most poignant moments in Ruby’s life came after Hollis’s Black father had earned medals of courage fighting for this country in World War II. Ruby’s father tried to return to his life in the tiny rural town where the family lived, but soon disillusionment overwhelmed him.

“World War II inspired Black men to work to gain freedom for their own families,” she said, “but Mama could no longer work as a nurse and became a domestic servant for a White family. When she began bringing us leftovers from that family, I realized there was a big difference between our lives and theirs.

“Daddy put his life on the line helping liberate Europe on the battlefield,” she explained. In Mississippi after the war, her father took his family to the bus stop to ride to a distant Mississippi town where soldiers from his battalion were commemorating their part in the war. “The bus driver refused to let us ride,” she said.

“I never thought you could question White folks,” Ruby said, “but after that, Negroes in the hundreds stayed off the buses for a full year. I decided my only chance of survival was to get as far away as possible and I applied to the best negro college, in Tougaloo, Mississippi.” She got a scholarship and began her studies. “Being there, I almost forgot what it was like to be Black in the south.”

On a trip home, Hollis and her cousin Michael put on their Sunday best and politely took seats at a lunch counter. “Stores let us buy things but wouldn’t let us sit to eat,” she explained, “and soon crowds surrounded us, spitting on us, pushing lit cigarettes into our backs. One man, accompanied by Jackie, threw acid in Michael’s eyes. He was blinded for life over a cup of coffee, she said. She asked her cousin, who returned to activism, “Haven’t you been hurt enough?” He said, “The movement for freedom still needs me, and you, too.”

Before she graduated, she came home on a break and helped spread the word about freedom. “We were passing out leaflets when White guys on the street cornered us,” she said. When a sheriff threatened to hurt her mother if she continued, she walked into the office of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), set down her luggage and asked what she could do.

“We were beaten every day, and still many Delta Negroes believed that only Whites were supposed to vote. When we marched people to the courthouse to register, the elections officials would question us on over 200 sections of state law, and they never were satisfied with our answers even though no one else could answer their questions.

“We had high school kids enthusiastically canvassing door to door when Medgar Evans was shot and killed in front of his house, she explained. “People would see us out at night and tell us that Whites were planning to bump us off. Parents began keeping the teens at home, and a few weren’t enough for change to take place.”

She recalled the March on Washington that August with its crowd of a quarter of a million people. But then four little girls praying in a Birmingham, Alabama, church were killed when it was bombed. She said that was when 1,000 northern White students put themselves in danger in what was called Freedom Summer. What followed was more violence, Blacks having to check their cars for dynamite, and then three freedom fighters were murdered and buried with a bulldozer.

“Playing by the White folks’ rules would only take us so far. Malcom X, who had inspired so many of our young people (but had become disillusioned with the Black Muslim movement), was killed three weeks after he came to help us.” So there was no time even to mourn the brutal death of Jimmy Lee Jackson, she said, explaining that he had tried to protect his mother from a White mob who was beating her.

During the subsequent famous March across the bridge from Selma, Alabama to Montgomery, troopers beat back the marchers, hitting them with night sticks and cattle prods. The late Congressman John Lewis, who was the head of SNCC at the time, was on the march from Selma to Montgomery and was badly hurt. Hollis’s brother Tony also was hit and his skull was cracked open, but police said they would not give medical help to Blacks.“

Hollis said, “That’s when Daddy joined us. He had been standing with us, listening to Martin Luther King, Jr speak. But after my father returned home, his body washed up on the river bank. Daddy didn’t die in vain. He had helped unlock the ballot box, and I vowed not to stay silent, so my name was on the ballot. I was running the race for city council for me, for Tony, Michael and all who did in this movement.”

“It’s time for things to change, again. What will you do?” she asked her audience.

Cornejo asked for questions and comments. Karen Pedey explained how impressed she was that big band director Benny Goodman had defied hotel owners who had made Black performers go through the kitchens.

A local teacher whose students were to see the presentation provided by the school district Monday said, “Sometimes we’re feeling righteous, but it gets in the way of compassion. I’ve never seen anyone respond to righteousness as they do to compassion. We need to look at how to teach that.”

Local entrepreneur and activist Kate Painter said she has learned the hard way that things come over social media more angry (sounding) than she means. “How do we communicate through social media in the way we want without it backfiring?” she asked Cornejo. The presenter said, “I’m most impressed when (people) keep to the facts.”

“We have to keep this history alive,” added Middle School art teacher Dawn Wagner. She explained that every year she teaches a unit focused on human rights.

Asked if there are young leaders stepping up now to support the right to vote, Cornejo noted that, sadly, to a large degree today’s young people are not willing to communicate in person. Part of that is their reliance on social media and Zoom-type meetings through Internet.

One woman told the actress that she had brought her to tears with her portrayal of Hollis’s life of hardship and courage. A couple came by as people were leaving, and the man told her the same thing.

Wow! What a moving event so rich with the proud history of the civil rights movement! Ty for sharing your article Clarice!

Catherine Hillery Swing Blue Alliance