By Mike Weland

By Mike Weland

About 100 people turned out at Bonners Ferry High School October 9 for a public hearing on a land use appeal that appears simple; an open and shut case of an individual buying a business in 2018 bound by the terms and conditions of a special use permit issued for its establishment in 2005, who did then expand said business without going through the process of amending that permit in clear violation of the Boundary County Zoning and Subdivision Ordinance and as noted on the permit itself.

But in Boundary County, few land use issues that grow contentious are ever simple.

In the 1970s, the Idaho state legislature mandated that all counties adopt land use laws or have the state step in and do it for them. Under the state mandate, every county in the state would develop and adopt a comprehensive plan, which is an analysis of several resource categories within the county as well as a general overview of how those resources ought to be considered when making land use decisions. Land use laws were then to be crafted to achieve the aims established by the comprehensive plan.

Boundary County officials, for the most part, detested the idea of putting limitations on what a property owner in their jurisdiction could or could not do on their property and fought against being forced to impose limitations. They gave in only when it appeared the state would make good its threat. And over time, they perfected a strategy of drafting land use laws that for the most part prohibit very little, but allow consideration, and approval, of nearly anything.

Coupled with very limited provisions for enforcement and you have a set of laws more akin to the Pirate’s Code as described by Captain Barbossa in “Pirates of the Caribbean, ” … the code is more what you’d call ‘guidelines’ than actual rules. Welcome aboard the Black Pearl, Miss Turner.”

For the most part, those “guidelines” have served the county well for most of half a decade. But when legitimate disputes arise, and there is no doubt that this is a legitimate dispute with the potential of blowing rapidly into a dispute of “Perfect Storm” proportions, the ordinance fails and provides nothing objective the deciding body can stand on, meaning any final decision they reach will be arbitrary at best, insufficiently supported by the county’s own laws.

Boundary County land use law worked in 2005 when Joel Martin and his wife, Lorna, filed P&Z application SUP 05-07 … the seventh special use permit application filed in 2005. The couple lived on a 20-acre parcel at what would become 168 Pothole Road … a terse bit of road off Highway 95 just south of the crown of Peterson Hill. It was owned not by the county, but by Don Jordan, who lived at 51 Pothole Road and gave the Martins free legal access to their property on a hand-shake agreement that the road would be used, at best, for single-family residential access, at worst for access to a small business.

Don later became an absentee land owner, having acquired a full and mutually shared interest in a new and exclusive partner, Kathy Konek, and moving across Highway 95 onto Brown Creek Road, always with plans to retire to a paradise accessed by a road later named in the tradition of local hunters telling out-of-towners the location of favored deer camps. Joining No Seeum Creek and Skunked Again Slough, Pothole Road was added to the lexicon of places for the trusting to stay away from as the name told you all you needed to know.

“While Maverick Lane at the south end of the subject property is permitted for multi-family residential access, Pot Hole Road does not hold any type of permit for access to US 95 and the parcel does not have a legal right to access US 95 commercially,” an ITD official wrote in response to Mast’s application. “Until such time as the property owner applies for and receives a permit for commercial access, the Idaho Transportation Department does not favor the proposed modification to conditional use permit File #05-07. Due to tight turning radius required for ingress and egress to Pot Hole Road from US 95, this location is not safe to provide access for commercial truck traffic to US 95. I have discussed this with Mr. Mast and while the financial responsibility for necessary improvements to US 95 belongs fully with the property owner, ITD will do what it can to assist in arriving at a reasonable but most importantly safe solution at a new location.”

Don was somewhat concerned when the Martins applied to establish a manufacturing business, Panhandle Kitchen and Door, as were many who lived in close proximity, but wrote the P&Z Commission in favor of it since it was to be under 10 employees.

On June 23, 2005, Jordan presciently wrote the planning and zoning commission, “I am unsure of all the advantages of the Conditional Use Permit vs a Rezone. I THINK the conditional use permit is a ‘better’ way to go and commend Joel and Lorna for requesting it. I would expect that the Conditional Use Permit will legitimize their operation nearly as well as a Zone Change, but if the use should change in 10, 20 or 50 years the Permit could be reviewed. As long as the use has half the quality of the Martin’s operation, I would hope and expect that the activity be encouraged.

“If the use was to drastically change, I think it is also appropriate that the permit be reviewed. I am not sure a Zone Change would offer as good an option for encouraging appropriate business while offering some recourse to the community in the rare event of an inappropriate operation by some other owner in 50 years ???”

Though the application was actually a special use permit, requiring two public hearings and decided by county commissioners with a recommendation from the planning and zoning commission, Jordan was correct; a zone map amendment would allow all the privileges of the zone, including setback requirements, while a conditional or special use permit retained the underlying zoning, but allowed the use specified, to include any limitations or restrictions listed on the permit. (Under the current zoning ordinance, special use permits have been eliminated.)

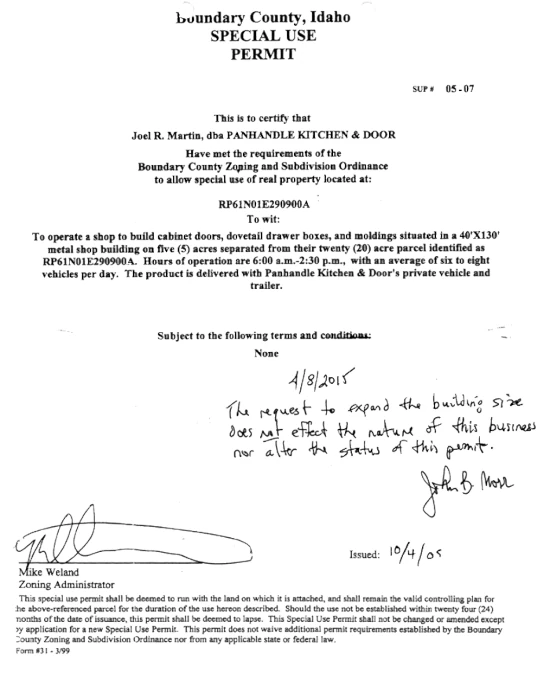

On October 4, 2005, Joel Martin was issued permit SUP#05-07, “To operate a shop to build cabinet doors, dovetail drawer boxes, and moldings situated in a 40’X130′ metal shop building on five (5) acres separated from their twenty (20) acre parcel identified as RP61N01E290900A. Hours of operation are 6:00 a.m.-2:30 p.m., with an average of six to eight vehicles per day. The product is delivered with Panhandle Kitchen & Door’s private vehicle and trailer.”

As with every special use permit issued, SUP#05-07 bore the footnote; “This special use permit shall be deemed to run with the land on which it is attached, and shall remain the valid controlling plan for the above-referenced parcel for the duration of the use hereon described. Should the use not be established within twenty four (24) months of the date of issuance, this permit shall be deemed to lapse. This Special Use Permit shall not be changed or amended except by application for a new Special Use Permit. This permit does not waive additional permit requirements established by the Boundary County Zoning and Subdivision Ordinance nor from any applicable state or federal law.”

For 13 years, Panhandle Kitchen and Door operated according to their permit with no complaints.

Then in 2018, Joel and Lorna divorced. Nelson Mast and Maverick LLC purchased the business, Panhandle Door, Inc. (PDI) was formed and amity between PDI and neighboring residents soon ended.

Kelli Martin, the daughter of Pothole Road retirees Frank and Judy Weston (and no relation to Joel and Lorna) left Bonners Ferry for Texas, her dad recovering from a broken femur but getting around well with the aid of a walker. David Newberry moved here with his family and soon purchased a home on Pothole Road and went to work at PDI.

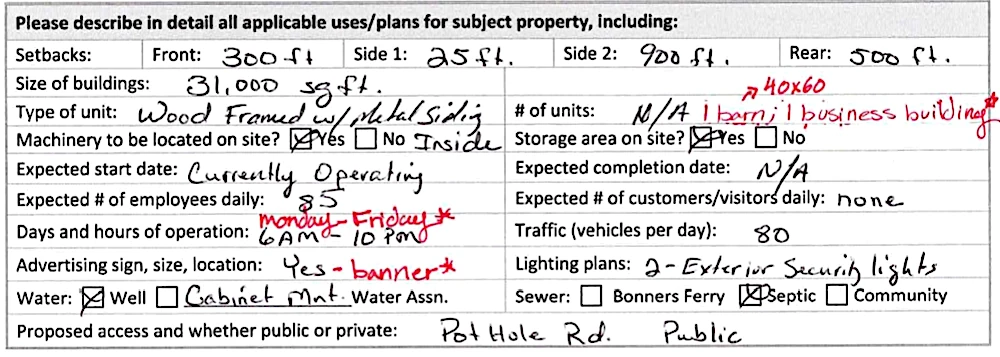

In the weeks and months that ensued, and with no notice to anyone, the PDI building was expanded from 1,200 to around 22,000 square feet, one wall of the building moving from 20-feet to within three feet of the property line of the Westons, closest adjoining neighbors. On the wall just above head level were large fan-driven vents blowing allegedly unfiltered noxious and caustic chemicals from paint booths straight toward the Weston’s bedroom window.

Traffic on Pothole Road increased to between 100 and 200 vehicles per day, and now included semis and big rigs hauling in allegedly contaminated fill dirt from city and county road projects to cover huge mounds of sawdust, treated wood, MBF and other waste that had once been burned, sometimes unintentionally.

A second shift was added, extending operating hours to late at night. Soon, more than 80 people worked there, making PDI one of the largest private employers in Boundary county.

(Article continues below)

And life for the once tranquil Pothole Road community took a decided turn for the worse. In August, 2022, Kelli came back after her mother told her she had stage four lung cancer. She barely recognized the beautiful parcel she left just four years earlier, and it didn’t take a doctorate in rocket surgery to identify the culprit; the trees that once formed a cozy and impenetrable nest around her parent’s retirement haven now felled, dead or dying, leaving a clear view of the wall of PDI, a large open vent spewing a noxious wet mist that coated the nearest vegetation in a sickly white, the fumes burning her throat and eyes as she tended her so recently healthy mother.

Less than a month later, Judy Weston was dead. Kelli’s father, Frank, died nine months later exhibiting nearly identical symptoms. Her brother-in-law, Jeff Love, who had dropped everything to come and help in January 2023, developed the same raspy dryness Kelli had heard in her parent’s voices, followed by a cough she’d heard so often of late. Jeff died on May 26, 2024.

Having both lived on Pothole Road and worked in management at PDI, Dewberry said he worked hard to get the company to both be better neighbors to the families that share Pothole Road and better employers to those who would work without concern for their own safety and wellbeing. Unable to agree, by mutual consent, they parted ways within a few years. He compiled records from multiple agencies documenting the growing list of allegations, sharing that information with anyone in a position to help.

Jeff lived long enough to see Kelli, Dewberry and other neighbors make formal written complaint to several of those agencies; county planning, ITD, OSHA, DEQ and more, to see county planners issue a notice of possible violation.

He was spared seeing his sister-in-law and neighbors disparaged as troublemakers for standing up to defend their interests, their investment, their rights, their homes. He was spared the indignity of being invited by the county to appear at a public hearing before the Boundary County Planning and Zoning Commission to speak for, uncommitted or against an application for a new conditional use permit, at a cost to PDI of $500 that would absolve from penalty or restitution all violations of the past six years and retain to the guilty all the profits and benefits derived therefrom, declaring the guilty in full compliance with a new piece of paper, the losses alleged by the surrounding property owners written off.

Enough complaints were made against PDI that Idaho Department of Environmental Quality surface water manager Robert Steed emailed colleagues on June 17, “Panhandle Door/Maverick in Naples seems to be a chronic dispute between neighbors although there may be merit to the claims … I think I remember more bad acting on the part of Panhandle Door/Maverick than I was able to find in complaint tracker.”

“Other than the sound of the exterior dust collector running and the traffic using the private road I don’t believe that we have created an impact that is any different than the surrounding zone,” Mast wrote in response to neighbor’s concerns. “I do not believe we are creating any adverse conditions on the surrounding land uses. The fact that we are and have been operating at this location since 2005 is proof this. We have not placed an unfair burden on local taxpayer or the community. On the contrary, I believe we are an asset to this community. Both through job creation and as a way to bring additional revenue to our community.”

He professed being told at the time of the purchase by then county zoning administrator John Moss that as long as the type of manufacture didn’t change, the permit would remain valid.

“There was never any mention of any restrictions required by the special use permit,” Mast wrote.

Moss said no such discussion took place.

The conditional use permit was approved unanimously in July, as expected.

And those affected neighbors, who had every right and reason to expect that the county, having memorialized a compact that “shall remain the valid controlling plan for the above-referenced parcel for the duration of the use hereon described” found themselves being appeased.

“Appeased.” Pacified and placated, their demands that the lawful terms and conditions as written with clarity in a single paragraph on a one-page legal agreement, entered into in accord with laws drafted and enacted by the duly elected and lawful governing body of Boundary County, Idaho, be upheld. They went away ignored.

Don Jordan and Kathy Konek and Dewberry, Martin and Jeff Steinborn each filed a formal appeal, both groups paying a $500 nonrefundable appeal application fee for one last chance short of a lawsuit to make an appeal to county commissioners to uphold their rights, to help them salvage what hadn’t yet been taken from them without their consent and against their will and to have at least some of what had been stolen restored.

As the process progressed, improvements were made. Stacks to elevate the exhaust were installed to lift the volatiles high enough to disperse before settling. Required filters are now in place. “Volatiles,” the chemical used mainly in the finishes applied to drawer facings (and which, Mast pointed out, are not dangerous or caustic once dried following application) are now trucked to Spokane for disposal, wood waste to Lewiston for conversion into hog fuel.

Mast says the steps he’s taken show his willingness to go to great lengths to be a good neighbor. Neighbors say they were steps taken to come into compliance with agency requirements that should have been in place from the outset.

Most of last Wednesday’s appeal hearing was typical — both sides citing ordinance and comp plan provisions to justify their assertions. PDI employees stood one after the other, testifying to how grateful they were to have such good jobs, such a good company to work for. One side spoke of how much PDI had cost the community, the other how much they’d given.

But there were two whose testimony stood out.

In the new conditional use permit under appeal, the planning and zoning commission deferred “to the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality for regulatory intervention” as regards air quality, which “shall be met for the life of the use: a. Boundary County shall defer to the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality for regulatory intervention. b. Fugitive Dust – All reasonable precautions shall be taken to prevent particulate matter (dust) from becoming airborne, as required in IDAPA 58.01.01.651. c. Open Burning – Open burning of trade waste is not an allowable form of open burning as defined by IDAPA 58.01.01.600. Trade waste includes any waste generated in the manufacturing process. d. Air Quality Permits – Panhandle Door, Inc. has an active air quality permit with DEQ. The landowner, applicant, or agents of the landowner or applicant shall follow all DEQ permitting requirements, including following their current permit and updating the permit as needed.”

But DEQ Regional Administrator Daniel McCracken told county commissioners that his agency should not be considered the county’s enforcement arm in such cases.

“DEQ is not in the business of shutting down businesses,” he said, saying that DEQ saw its mission of compliance as a process that was ongoing rather than a status achieved. PDI, he said, has several air quality violations, but is cooperating adequately to resolve them. Some may take up to two years to fix.

He said no air quality monitors were required at PDI, those being reserved for operations five times larger, and that PDI was in no danger of triggering DEQ’s most extreme penalty, a $10,000 per day per violation civil fine.

And then Kelli Martin rose to give her closing statement. She spoke for the first time of the loss of her parents, her brother-in-law, of she and her daughter, just 18, both having developed that dry, raspy voice, both now undergoing tests for chemical abnormalities, both having to wear heart monitors. Of her being so fearful she drafted her will to spare her children at least some of the anguish she’s endured.

“Now I ask why didn’t this meeting take place six years ago?” she said. She pointed out the number of similar businesses operating without problem or controversy in areas of the county zoned for such use. Mast, she said, could have saved the taxpayers the cost of these hearings and his employees the fear and uncertainty they are facing now had he only taken county zoning laws seriously and followed them.

“How can a family living approximately 100 feet away from the off gassing coming straight out the side of the building with blowers that employees confirmed had no filters, after a third death all within nine months of each other, accept that it was just a coincidence?” she asked. “Animals with tumors and dead from masses on the lungs? ‘Mom,’ my daughter asked me, ‘is it going to take one of us kids to die for people to care?'”

There’s a conundrum in such cases that not only frustrates the appellant(s) but can actually hamper their ability to present their case effectively. Conversely, that conundrum can contribute to turning a maelstrom into a perfect storm.

There’s a conundrum in such cases that not only frustrates the appellant(s) but can actually hamper their ability to present their case effectively. Conversely, that conundrum can contribute to turning a maelstrom into a perfect storm.

Despite the fact that few who serve on planning and zoning commissions, city councils or county commissions are trained in the law, as are even fewer who are parties to land use disputes, the hearings by which they are decided are deemed “quasi-judicial,” meaning “court-like,” to ensure that all affected parties are afforded “due process,” the fair and impartial application of the law so as to protect a person’s rights.

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside,” reads the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

On the table at which commissioners and other principals sat Wednesday evening were multiple five-inch binders, each copies of the “evidence” compiled by Dewberry, delivered in time to meet the deadline for written submissions specified in the notice of hearing. But it’s unlikely anyone read the massive tranche, even though, as Steed wrote his staff regarding material brought to his attention, “there may be merit to the claims.”

In a court of law, each bit of evidence in a criminal or civil case is carefully and meticulously introduced, a foundation laid attesting to its authenticity, its relevance, competency and materiality. It is appropriately distributed so all parties have opportunity to consider and respond. Such rigorous standards don’t apply in a quasi-judicial proceeding, however, there are general guidelines to be followed in accepting evidence to ensure it meets evidentiary standards.

As in a court of law, decisions in a quasi-judicial proceeding must be based on evidence, not personal preferences or emotions.

On Wednesday, county commissioners tabled the hearing having accepted considerable testimony, but very little evidence. They did so for the purpose of obtaining evidence.

“Commissioner Robertson moved to continue the hearing on November 6th at 6:30 p.m. at the Bonners Ferry High School auditorium for clarification on ventilation hazards, tests for air quality and clarification from ITD on new access,” meeting minutes read. (The date is now pending as the Becker Auditorium had previously been booked.)

It has also not been decided who is to provide the information, or at whose expense. Typically it would be the respondent, in this case PDI.

Unless the hearing is reopened to public comment, no one, to include the appellants and the respondent, will have the ability to respond to or counter any evidence submitted. The appellants say they’re not willing to accept anything on faith at this point.

“(Commissioner) Ben (Robertson) wants an air sample, yet Vern ( PDI manager Vern Helmuth) said they double filtered it,” Kelli said. “If they got an air sample a month ago, it would be deadly telling. Mast would have to be forced to show a compliance officer records monthly of Safety Kleen. We don’t have a compliance officer, as you know.

“How come Tessa did not put evidence pictures of cement, rebar and plywood up on the screen that we provided, nor the SDS sheets of toxic chemicals to allow the audience to see proof? Who chooses the pictures and information to share with the public?”

No matter the final decision rendered, the dynamics of this case have the potential to cost Boundary County and her citizens considerably, be that by the high cost of litigation should Pothole Road residents file suit in an attempt to be made whole by the county whose laws contributed to their demonstrable losses or by the possible loss of 85 jobs and a business whose owner saw a door of opportunity left wide open by the county and walked through, gaining a slight edge of short duration over competitors who chose to abide the well-intentioned spirit of the county’s land use guidelines rather than the ambiguous letter of the law.